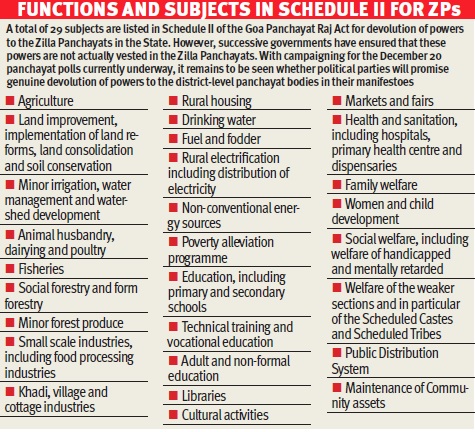

Crores released, but 29 mandated subjects still not devolved, reduced to ceremonial bodies

Members of the South Goa Zilla Panchayat had to literally function without the constitutionally-mandated powers and functions.

MARGAO

In the run-up to the Zilla Panchayat polls, a flurry of activity was evident across the South Goa countryside. Zilla Panchayat members appeared preoccupied with inaugurating interlocking pavers, water coolers, sheds at religious places, and similar small-scale works.

The South Goa Zilla Panchayat, on paper, has an impressive record: Close to 1,000 projects, 961 developmental works to be exact, executed across its jurisdiction over the last five years. Funds were clearly not a constraint. The Zilla Panchayat reportedly received a record Rs 84.35 crore in grants from the government and under the Finance Commission during this period.

Yet the real and uncomfortable question remains deliberately unaddressed: Did the government devolve even a single one of the 29 subjects and powers to the Zilla Panchayats, as mandated under the Goa Panchayati Raj Act and the 73rd Constitutional Amendment? Or were Zilla Panchayats merely pacified with grants, while being systematically denied authority by successive governments through the release of financial grants, without any meaningful transfer of powers?

Successive governments have, in fact, assiduously ensured that Zilla Panchayats — set up two decades and half ago in the year 2000 — have not been vested with the powers and functions envisaged under the 73rd Constitutional Amendment.

In their initial years, Zilla Panchayats were entrusted — albeit begrudgingly — with limited responsibilities such as repairs and maintenance of primary health centres, government primary schools, and minor irrigation works. Even then, their role was so constrained, leading many to describe the district panchayat bodies as little more than the “repair wing” of the Public Works Department.

But even this token empowerment did not last. Sources pointed out that these limited functions were quietly withdrawn, rendering the Zilla Panchayats virtually defunct. Reduced to ceremonial bodies, these constitutional institutions today have little to do beyond laying interlocking pavers, supplying water coolers to schools, repairing minor roads, etc.

Panchayati Raj activist J Santan Rodrigues does not mince words. “This is not decentralisation; it is deliberate disempowerment. While governments claim adherence to constitutional principles, Zilla Panchayats in Goa remain trapped in a system designed to keep power firmly concentrated at the top — leaving grassroots democracy as nothing more than a convenient slogan during election season,” he says.

A former member of the South Goa Zilla Panchayat, Rodrigues was also instrumental in taking the fight for devolution of powers to the courts over a decade ago. He squarely blames successive governments for denying Zilla Panchayats their rightful authority. “Just imagine — Zilla Panchayats in Goa have completed 25 years, yet the powers and functions envisaged under the Goa Panchayati Raj Act are still to be devolved to these district panchayat bodies,” he adds.

One draft development plan in 25 years, but confined to books

MARGAO: Despite the constitutional mandate under the 73rd Constitutional Amendment and the provisions of the Goa Panchayat Raj Act, Zilla Panchayats in Goa continue to be largely sidelined in the district-level planning process — a situation perpetuated by successive State governments.

Article 243ZD of the Constitution provides for the constitution of a District Planning Committee (DPC), chaired by the Zilla Panchayat Chairperson, to prepare an annual draft development plan for the district. The plan is to be drawn up by consolidating proposals received from Zilla Panchayats, village panchayats, and Municipal bodies, and then forwarded to the State government for implementation.

But how many such draft development plans have the South Goa District Planning Committee prepared in the last 25 years since the Zilla Panchayats were constituted in Goa in 2000? The answer: just one.

The South Goa DPC managed to prepare a draft development plan only once — for the financial year 2024-25 — under the leadership of then South Goa Zilla Panchayat Chairperson Suvarna Tendulkar, when Florina Colaco was serving as Chief Executive Officer of the South Goa district panchayat. However, the consolidated draft plan failed to find favour with the Goa government and remains unimplemented to date.

With the fate of the 2024-25 draft development plan still unclear — sources claim it is gathering dust in government files — the planning process in South Goa has effectively come to a standstill.

Officials say the government’s lukewarm response has discouraged the DPC from initiating the planning exercise for the financial year 2025-26, fearing that any fresh plan would meet a similar fate.

The South Goa DPC has also come under pressure from panchayat bodies and Municipal Councils, which are seeking clarity on the status of the development plans they had submitted to the district planning body for implementation. “How could the DPC begin the process for the new financial year when panchayat bodies are questioning us about the fate of the plans submitted last year?” a senior South Goa Zilla Panchayat official remarked.

As a result, a constitutionally-mandated planning mechanism in South Goa appears to have stalled, raising serious questions about the State government’s commitment to decentralised planning.