In Goa, there remains a generation that became Indian citizens after liberation while their names continued to appear in Portuguese registers as an administrative legacy

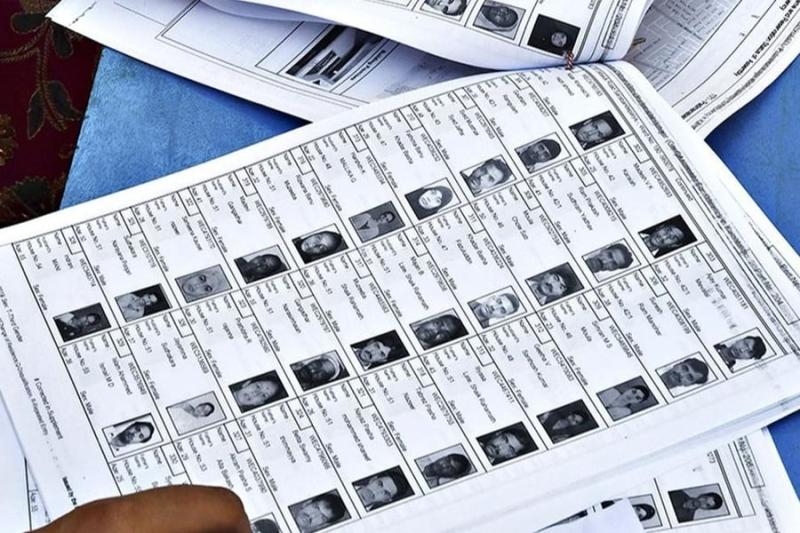

The ongoing Special Intensive Revision in Goa has been announced as an administrative exercise to update the electoral roll. The process draws its authority from Article 324 of the Constitution, Section 21 of the Representation of the People Act 1950, and the Registration of Electors Rules 1960. It is intended to ensure that every eligible voter is correctly recorded and that entries of those who have died, shifted or otherwise ceased to qualify are rectified. What places SIR apart from the annual summary revision is the requirement of house-to-house verification. Enumeration forms are issued and electors are asked to re-confirm personal particulars, residence and other details.

This process is designed to strengthen voter rolls and to support a transparent election system. Yet in a territory like Goa, SIR inevitably intersects with questions of citizenship arising from the region’s distinctive history.

Electoral rules and

citizenship

While the electoral roll must contain only citizens of India aged eighteen years or above who are ordinarily resident in the constituency, the authority to decide who is and is not a citizen has been placed by Parliament in the Citizenship Act 1955. Section 9 of that Act vests power in the Central Government to determine whether an Indian has ceased to be a citizen by voluntary acquisition of foreign nationality.

In contrast, the powers of Booth Level Officers and Electoral Registration Officers under the Representation of the People Act extend only to the maintenance of voter lists. These officers may add, correct or delete names on grounds related to residence, age or disqualification. They cannot presume, declare or adjudicate on the fact of foreign citizenship.

SIR must therefore be understood as an exercise concerning voter eligibility rather than an inquiry into nationality. When a verification process extends to probing the ancestry or documentary history of electors in a region shaped by colonial transitions, a risk arises of an administrative process taking on the colour of a citizenship tribunal. In any democracy, that overlap must be avoided to preserve constitutional boundaries.

Goa’s colonial legacy

Goa’s experience as the former Portuguese Estado da Índia left behind extensive civil-registration practices. Births were recorded in the Portuguese Registo de Nascimento. Identity cards such as the Bilhete de Identidade were issued, and some entries continued to be carried forward long after the liberation of Goa on December 19, 1961. Portugal did not immediately recognise India’s sovereignty over the territory and maintained civil registers for several years.

As a result, an older generation of Goans found themselves listed in Portuguese registries without any voluntary action on their part. The presence of a Portuguese record or an ancestral document did not reflect a conscious decision to acquire Portuguese nationality. This continuity of documentation is a historical remnant rather than a marker of foreign allegiance.

During SIR, when officers encounter questions about inherited identity documents, there is a danger that suspicion may be raised where none is warranted. If the exercise is applied without sensitivity to the history of colonial carry forward, long-resident Indian citizens risk being treated as if they had renounced their nationality, even though no such voluntary act occurred. Careful distinction between involuntary inherited records and actual foreign citizenship is essential.

Lessons from

Puducherry

A similar dilemma is present in Puducherry, which incorporated four former French colonies. Under the Indo-French arrangements, residents were once allowed to retain French nationality. Even today, many inhabitants hold French documentation while remaining long-term residents in India. When SIR commenced there, concerns were raised regarding the treatment of French-linked records in voter verification. The situation illustrated how former colonial enclaves require heightened care during electoral revision to ensure that eligibility is assessed correctly and without prejudice to complex identity histories.

Daman and Diu as

sister territories

Daman and Diu, which also formed part of Portuguese India, have similar patterns of archival presence in Portuguese civil registers. Here too, continuity of old identity documents has persisted across generations. These territories fall under the same national SIR framework and the same statutory provisions govern voter eligibility. The challenges that arise in Goa apply equally to them.

Recognising this shared past highlights the importance of consistent, constitutionally faithful application of the law. Electoral officers must focus on present eligibility criteria, and where documentary ambiguities emerge, they must avoid assuming that older Portuguese records prove foreign nationality. Their duty is to maintain correct rolls, not to determine citizenship status.

Constitutional boundaries

The Supreme Court has held that the ECI is subject to judicial review as a public authority. This means that its directions and the actions of officers under its supervision must be consistent with the Constitution and with statutory limits. When SIR is implemented, care must be taken to ensure that verification stays within the remit of electoral law. Officers must follow the procedure for claims and objections, provide opportunity for hearings, and record reasons for any deletion. These safeguards act as the necessary checks during SIR.

Where an ambiguity arises regarding nationality, the proper course is to refer the matter to the authorities empowered under the Citizenship Act rather than to decide the issue at the level of voter lists. Such an approach preserves institutional boundaries and strengthens trust in the revision process.

The position of

involuntary holders

In Goa, there remains a generation that became Indian citizens after liberation while their names continued to appear in Portuguese registers as an administrative legacy. They hold Indian passports and identity documents and have lived their lives as Indian citizens. For them, SIR must operate with clarity, restraint and appreciation of history.

If the revision is conducted in a careful and transparent manner, with sensitivity to involuntary colonial records, the objective of an accurate electoral roll can be achieved without excluding those who never voluntarily acquired foreign nationality.