Toddy tapping is one of the oldest occupations in Goa, alongside fishing and farming. This traditional practice has been crucial for countless families, providing a significant source of livelihood and ranking second only to rice harvesting in importance. The sweet sap, collected by traditional tappers known as rendeiro or rendeir, comes from both Catholic and Hindu communities, reflecting the rich diversity of Goan culture.

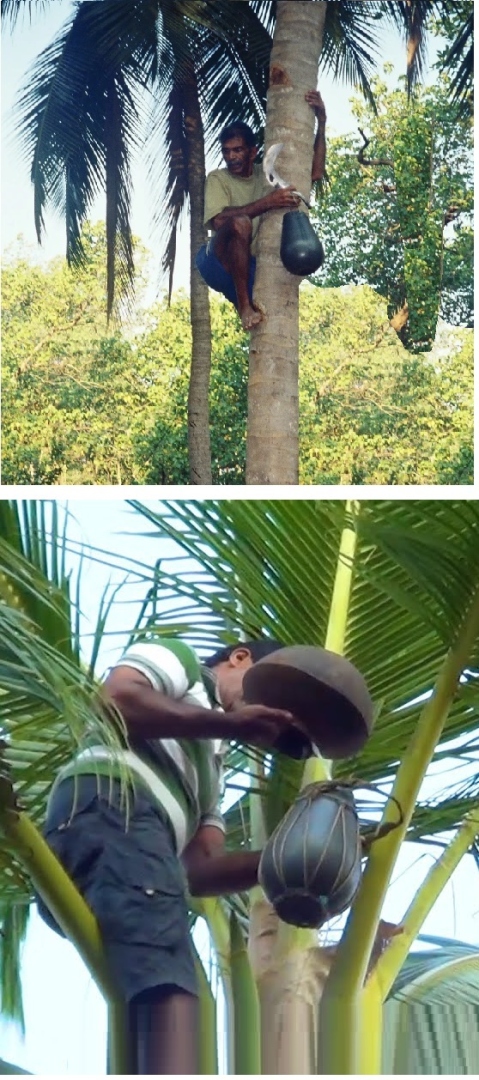

Collecting sap, or sur, begins early in the morning and continues in the evening. The rendeir climbs 5-8 meter tall coconut trees by carving grooves into the trunks. Climbing barefoot, a method passed down through generations, reflects their deep connection to the craft and the trees. Traditional rendeirs are equipped with a sickle or kathi, a dudhinem, and a kollso.

The sap is extracted from clusters of unopened flowers, or poi, through zig-zag cuts made with the kathi. Each poi is tied with vaie, strands made from treated coconut leaves. This sap trickles into an earthen vessel called a dammonem. Toddy is collected twice daily, with each pot yielding about 13-15 liters.

In the afternoon, the rendeir climbs the trees again to prepare the fronds using a broad, curved blade called a kathi. This preparation is essential for maximizing sap yield during the evening collection. The process requires skill and dedication, emphasizing the deep connection between the tappers and the trees they tend.

Goan cuisine is incomplete without its magical ingredient—vinegar. Vinegar fermentation is both an art and a science, rich in history and heritage. For home fermentation, the toddy is filtered through a dry muslin cloth into a stoneware vessel called a buyão. Some prefer using bellied, tinted glass bottles known as garrafão. A piece of red-hot roof tile may be added, while others opt for a burnt piece of bangle-shaped bread called kakonn. The buyão is then covered with a muslin cloth and left undisturbed for 22 days.

After 22 days, the mixture is tasted for tartness. As fermentation progresses, these bacteria form a white, cellulosic film over the toddy, known as “mother vinegar,” signaling its transformation into vinegar. The mixture is then strained and transferred into glass bottles or garrafãoes.

The sap, or sur, is in high demand—especially during festive occasions when people seek it to prepare sweet sannas (idly) or for vinegar. It is also used to make palm feni. A container of 18 bottles hardly costs around Rs 1000 while that of pure palm feni is sold for around Rs 7000-8000.

Vinegar serves multiple purposes beyond its culinary applications. It is commonly used as a disinfectant for wounds and burns, as well as a kitchen cleaner. In Goan Catholic cuisine, vinegar is an essential ingredient and preservative. Unique to toddy, coconut feni can be served in various flavors like dukhshree, lemongrass, and cumin seeds, unlike cashew feni. The sap is also used to make jaggery.

A popular spice mix, recheado, made from dried red chilies and spices ground in vinegar, is used to stuff fish like mackerel and pomfret. Dishes like sorpatel, vindalhos, Goan tossed salad, feijoada, and sweet and sour prawns all depend on this exotic vinegar, a product of dedicated rendeirs.

A dying profession

Once, it was common to find a rendeir in nearly every second house in Goa’s villages, but now the number has dwindled to just five to ten in each village, if not fewer. Many villages across Goa have no rendeirs at all.

According to the All-Goa Toddy Tappers Association in Margao, there are less than 200 active rendeirs left today. With around 3,000 members registered as OBC, there is a vital need for support to preserve this traditional craft and safeguard Goa’s cultural heritage.

Given the hard work and risks associated with the profession, today’s youth are often reluctant to enter the toddy-tapping business. The income generated from this work is typically modest, just enough to support a family, which further discourages younger generations from pursuing this traditional craft.

As the market for local products diminishes, promoting traditional Goan beverages is vital. Demand for local palm feni has shifted to more affordable brandy and whisky, reflecting changing consumer preferences and increasing pressure on traditional toddy tappers.

Toddy tapping depends on factors like weather and wind. The kathi is made by only one person in Goa, and potters have nearly vanished, making it a tough time for the industry. A decade ago, a rendeir would collect around 15-20 liters of toddy per day from 15 trees, but this yield has decreased due to climate change and other environmental factors.

Moreover, many mega-housing projects have significantly reduced coconut tree cover, impacting the environment and traditional livelihoods. This loss threatens the heritage of toddy tapping and disrupts local ecosystems that depend on these trees.

A way forward...

The ancient art of toddy tapping is experiencing a revival, but recognizing it as a prestigious profession vital to Goa’s Intangible Cultural Heritage is essential to fostering community pride and attracting younger generations.

The government should promote toddy tapping through cultural events, workshops, and educational initiatives that can raise awareness of its significance and help preserve this tradition. Supporting these efforts honors the hard work of traditional tappers and reinforces Goan culture’s unique identity. Pension support for aged and incapacitated rendeirs is the need of the hour.

With few rendeirs are left in Goa, the young Ms. Shweta Gaonkar stands out as the only female tapper in the masculine fiefdom. A graduate in agriculture from Sanguem taluka, she climbs 40-50 coconut trees daily using the climbing machine. She believes that even tending to just 10 trees can provide a lucrative annual income of Rs3-3.5 lakh, highlighting the potential of this craft.