A Map of Persia from 1800 (credit: http://iranpoliticsclub.net/).

British interest in the Persian Gulf originated in the sixteenth century when the British fleet supported the Persian emperor Shāh Abbās, aka Abbas the Great (1571-1629) the 5th Safavid Shah of Iran, in expelling the Portuguese from Hormuz Island in 1622. In return, the Safavid ruler issued a farman, or a royal decree from an Islamic ruler, allowing for certain trading rights to the British East India Company which was permitted to establish a trading post in Bandar Abbas, or Bandar-e 'Abbās, a port city on the southern coast of the Persian Gulf. Over time, this became their principal port in the Persian Gulf.

The influence of The East India Company in Persia greatly expanded with the ascent of an upstart military commander who seized power and became king, Nader Shah Afshar (1688–1747). Emperor Nader Shah, famous for defeating the weakened Moghul Emperor Muhammad Shah and ransacking Delhi, declared himself the Shah of Iran (1736–47) replaced the last Shah of the Safavid dynasty and started the Afsharid dynasty.

In 1763, the British East India Company established a political residency in the Persian Gulf at Bushire/Bushehr, on the Persian side of the Gulf; this was followed by another residency in Basar several years later. Subsequent farmans issued by later Shahs included the right of Englishmen to be governed by English rather than Persian law while living in Iran.

In the early part of the nineteenth century, looking to create a potential buffer for the defence of India from the Russians, Britain provided military assistance to the Crown Prince Abbas Mirza of Persia in his struggle against Russian expansion into the Caucasus. This resulted in the ratification of a Preliminary Treaty in June 1809. Revised in 1812 and 1814, the treaty provided for a subsidy to be paid by the East India Company to train and equip the Persian armed forces in Bushire/Bushehr and Tabriz, among other locations.

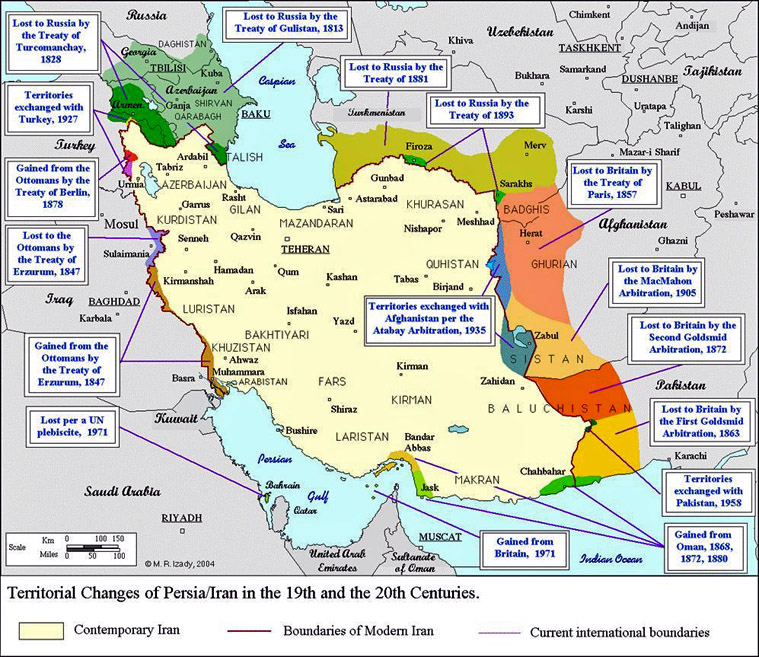

However, when French Emperor Napoleon invaded Russia in June 1812, it caused the British to abruptly stop their military support for Persia in their war against Russia. Napoleonic France was seen as a clear and present existential threat to the Island nation and Russia was now seen as a vital ally for Britain. Without European support, the Persian empire had to cede large swathes of its territory in the eastern Caucasus to Russia, including much of the modern-day states of Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the Russian Republic of Dagestan. Following further a military defeat in 1828 and the subsequent Treaty of Turkmenchay, Persia ceded the last of its remaining Caucasian provinces to Russia.

With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the British were able to revisit their priorities in the Persian Gulf. By 1817, the Qawasim pirates were spreading terror along the Indian coast within 70 miles of Bombay. This threat triggered a British military expedition in 1819, which crushed the Qawasim confederation and resulted in ratifying the General Maritime Treaty with Persia on 5 January 1820. Through extension and modification, this treaty formed the basis of British policy in the Persian Gulf for a century and a half until the Independence of India in 1947.

British interest in Persia became markedly more pronounced after the 1901 D'Arcy Concession between William Knox D'Arcy and Mozzafar al-Din, Shah of Persia which gave D'Arcy the exclusive rights to prospect for oil in Persia. The prize discovery of oil in Masjed Soleiman in 1909 was hastily followed by the establishment of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) when these rights were bought out by the Burmah Oil Company.

This British monopoly over Iranian Oil continued until 1951 when the charismatic Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh nationalised Iranian oil and booted out the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. This was a major success in asserting Iran’s national interests, but Mossadegh paid a heavy price for his efforts and was removed from office in 1953.

John Correia-Afonso notes that the British preferred hiring Goans because they could educate themselves quickly and perform a wide range of tasks from domestic staff such as cooks and butlers to highly trained professionals such as accountants, teachers and medical doctors.

According to one source, this created an opportunity for Goans who worked in various capacities in Iran, Kuwait, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, Aden, Bushire/Bushehr, Abadan and Basra. There were about 1,200 Goans fondly called ‘Basurkars’ in Bagdad, Basra, Abadan, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia in 1956. A Basurkar earned his salary in Indian Rupees. The Indian Rupee then served as the traditional currency in the Gulf and Trucial States (now called the United Arab Emirates).

From Studies in History-Atabaki-Far from home, but at home: ‘When the first stone of the refinery was laid in 1910, the island of Abadan was thinly populated by the Nassar Arabs. The migration to Abadan of people seeking employment in the oil industry soon grew beyond all expectations—especially after the First World War when the global dependency on fuel oil significantly increased. APOC’s Indian employees in Abadan numbered only 80 in 1910, but gradually rose to 1028 in 1914, and then grew sharply to 3816 in 1922.

[The writer is an engineer who retired in Silicon Valley. His interests include blogging, gardening, nature photography and travelling]