The history of the printing press in Goa is significant, as it marks the introduction of printing technology to India and Asia, driven by Portuguese colonial and missionary activities.

16th–17th Century

The first printing press in India, and indeed Asia, was established in Goa in 1556 by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries. This was facilitated by the arrival of a printing press at St. Paul’s College in Old Goa, where Printing was primarily controlled by the Jesuits and the Portuguese administration. The press was likely sent from Portugal under the patronage of King João III to aid evangelisation efforts among local populations. The output was modest, with only about 20–30 known titles printed between 1556 and 1670.

The earliest known printer in Goa was Juan de Bustamante, a Spanish Jesuit trained in Europe, and assisted by Indian workers. The press, primarily used to spread Christianity, produced religious texts in Portuguese and local languages. The first documented work was Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da Índia (1563) by Garcia da Orta—a Portuguese Jewish physician, naturalist, and pioneer of tropical medicine—a groundbreaking treatise on medicinal plants. Earlier prints, likely catechisms or pamphlets, are now lost. Notable early works include Doutrina Christam (1578–79) by Fr. Thomas Stephens, printed in Roman Konkani script—one of the first printed books in an Indian language—and Arte da Lingoa Canarim (1640), the first Konkani grammar, intended to aid missionaries.

Early printing in Goa faced major hurdles: scarce resources like paper and ink had to be imported, and skilled local printers were lacking. Strict censorship by the Portuguese Inquisition limited content, while traditional manuscript copying remained popular. These factors—logistical, technical, and cultural—slowed the growth of printing, despite Goa’s pioneering role in introducing print to Asia.

Late 17th–18th Century

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, printing in Goa experienced a marked decline. One of the key reasons was the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portuguese territories in 1759, which severely disrupted established printing operations. This was compounded by Goa’s broader economic and political downturn as a Portuguese colony, which limited the availability of resources and support for printing. Meanwhile, the growth of printing presses in other parts of India, such as Bombay and Tranquebar (a place on the Coromandel coast, Tamil Nadu), shifted attention and activity away from Goa. As a result, printing in Goa nearly came to a halt, with little to no significant output recorded during the early 1700s.

19th Century

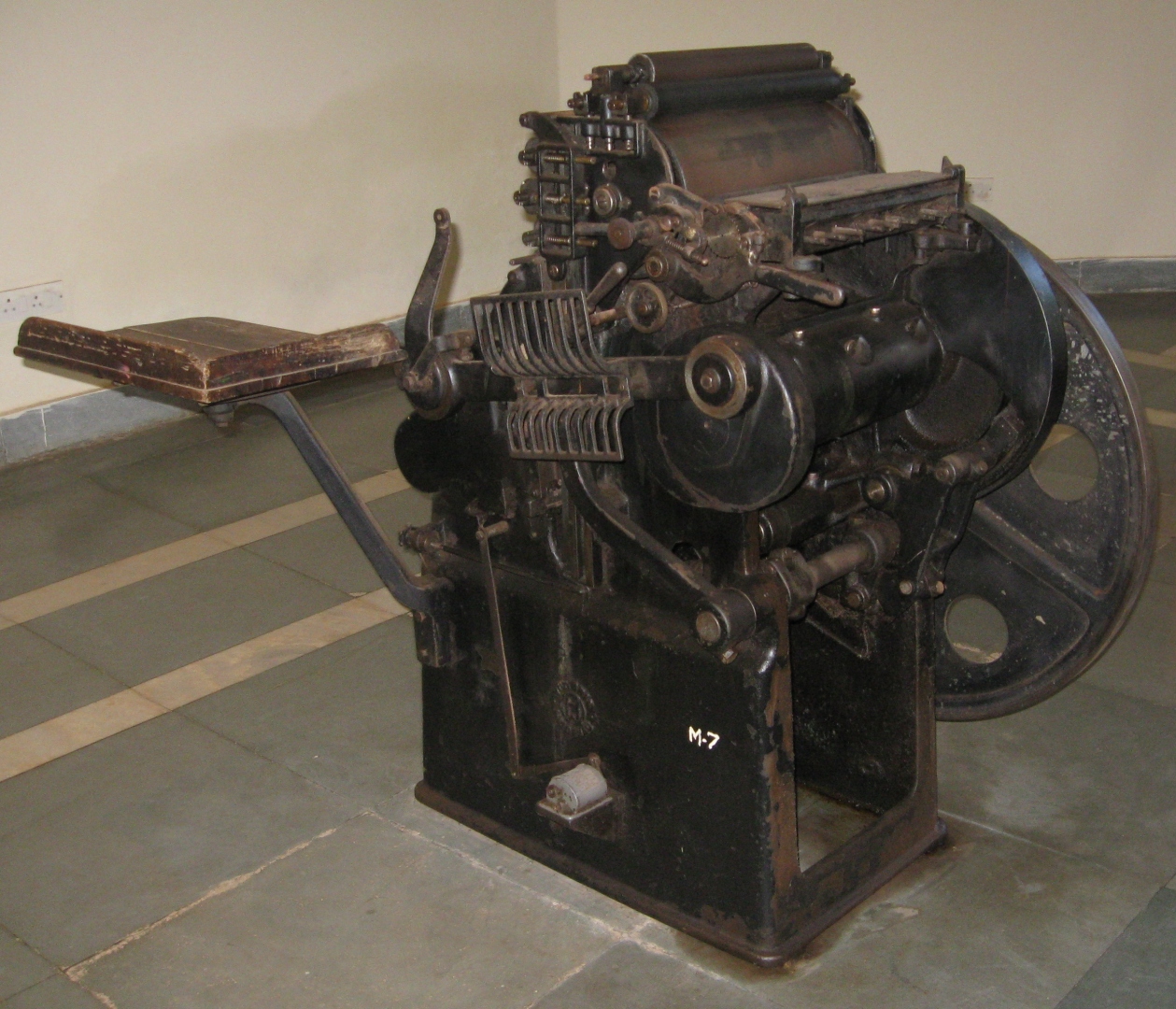

Printing in Goa experienced a revival in the early 19th century, spurred by the liberalisation of Portuguese colonial policies and the introduction of new printing technologies. A major milestone was the establishment of the Imprensa Nacional in 1821, which ushered in a new era of publishing. This state-run press was instrumental in producing official gazettes, legal documents, educational materials, and literary works, thus laying the foundation for a more informed and literate society.

Around the same time, private press began to emerge, catering to the growing demand for printed material among the expanding educated and urban middle class. This period also witnessed a surge in printing in regional languages—particularly Konkani (in both Roman and Devanagari scripts) and Marathi—which played a significant role in preserving and promoting Goan cultural and linguistic identity.

Newspapers like O Ultramar (1859) and A India Portuguesa reflected diverse views and helped shape Goa’s public sphere. Secular literature—poetry, fiction, and political pamphlets—flourished, especially after the 1822 Portuguese constitutional reforms, marking a shift from religious to more varied printing in Goa.

20th Century and beyond

By the early 20th century, Goa had a thriving printing industry centered in Panaji, Margao, and Mapusa, producing newspapers, books, and pamphlets in Portuguese, Konkani (Roman and Devanagari), Marathi, and English. This multilingual output reflected Goa’s diverse identity and played a vital role in shaping public opinion and supporting sociopolitical awakening.

The industry fueled Goan nationalism and anti-colonial sentiment through newspapers and literary magazines. Vauraddeancho Ixtt, founded in 1933 by Jesuit priests Fr. Arsencio Fernandes and Fr. Graciano Moraes, promoted Konkani culture and remains Goa’s oldest Roman script publication.

Tipografia Rangel, established in 1886 in Bastora, became renowned for regional literature and continues to operate as a symbol of Goa’s literary heritage.

Post-liberation in 1961, Goa’s printing industry modernised with offset and digital technologies, continuing to support education, journalism, and literature while preserving its historic print legacy.

Post-liberation - a new chapter of press

After Goa’s liberation in 1961 and integration into India, its printing and publishing sector entered a vibrant new phase. Freed from colonial restrictions, local publishers embraced democratic freedoms and adopted offset and later digital technologies, improving efficiency and reach.

A key milestone came in 1987 when Konkani was declared Goa’s official language. This led to a literary revival, especially in Devanagari. Roman-script Konkani publications like Gulab (1983), Vauraddeancho Ixtt, Udentechem Sallok (1889), and periodicals such as Sanjenchem Neketr (1907, Mumbai), Dor Mhoineachu Rotti (1914-15), Ave Maria (1919), and Udenteche Neketr (1946) also played a vital role in sustaining Konkani’s literary tradition.

Independent publishers, cultural institutions, and literary groups continue to enrich Goa’s print culture, preserving its linguistic and historical heritage for future generations.

(The author is a scientist and also works as a freelancer)