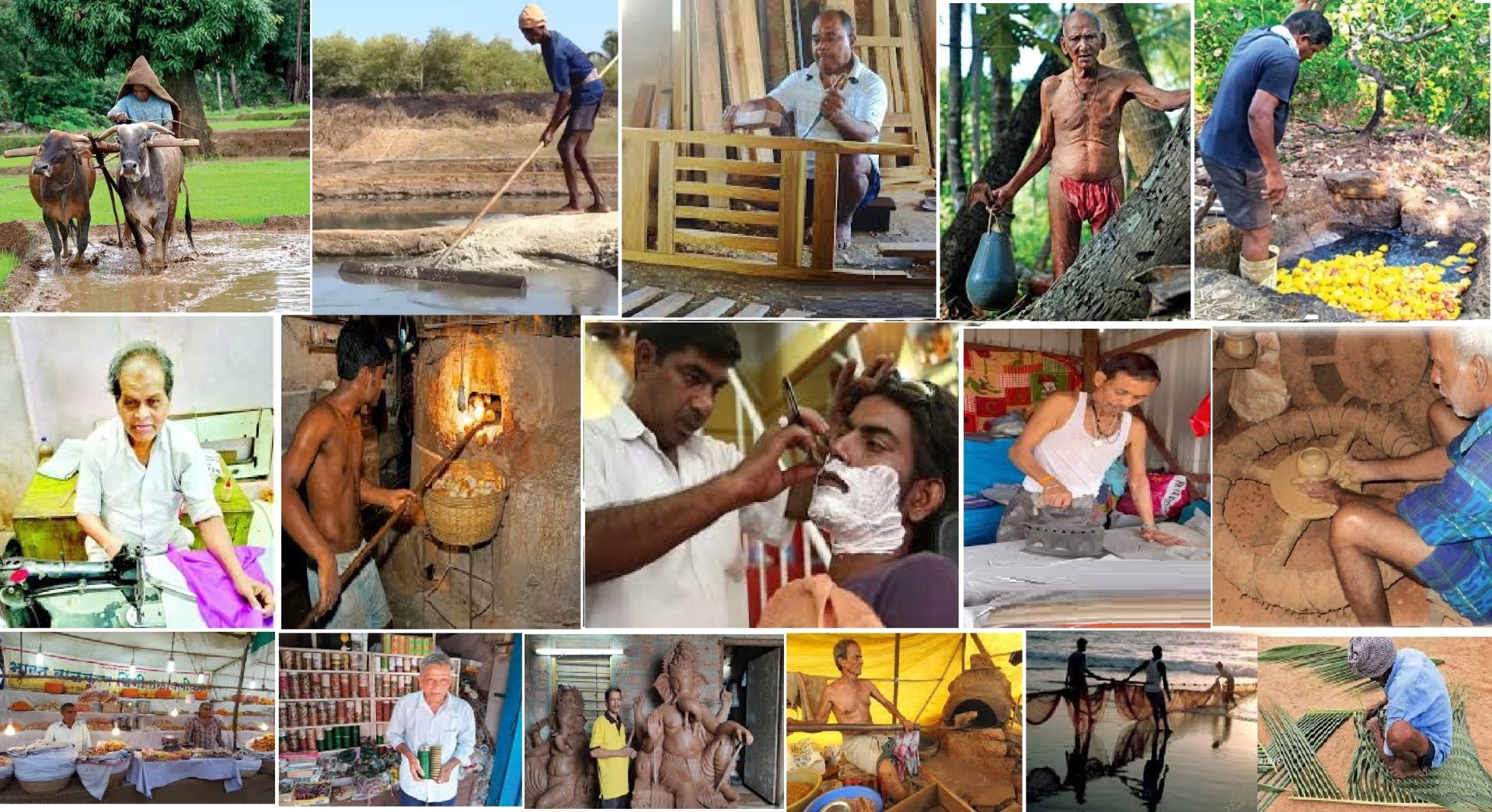

The traditional Goan occupations such as Xetkar (farmer), mithgaudi/agorkar (salt producer), thevoi (carpenter), rendeiro (toddy tapper), padeli/paddekar (coconut plucker), dongorkar (cashew farmer), dorji (tailor), podeiro (baker), mhalo (barber), modov (dhobi), kumbhar (potter), mali (gardener), khajekar (sweetmeat maker), Chonnekar (gram), chambhar (cobbler), kasar/tambat (coppersmith/brass and copper vessel maker), koloikar (possibly broom or coir worker), ramponkars (beach fishermen), kaknnakar (bangle/glass worker), mahar (bamboo/cane artisan, often Scheduled Caste), vanxekar (beam maker), Goddkar (coconut jaggery maker), razukar (coconut husk rope maker), Molamkar (matted coconut leaf maker), Randpi (village food caterer), Suin (midwife), Chiro taspi (laterite stone dresser), Murtikar (idol maker/sculptor), and Bhomkar (khazan bund/embankment builder/repairer) are deeply rooted in Goan society.

In the pre-colonial era, these traditional occupations formed the backbone of a self-sustaining agrarian and artisanal economy, deeply intertwined with the Gaunkari/Comunidade that ensured communal land management, resource sharing, and hereditary skill transmission among indigenous communities such as the Kunbi, Kharvi, and Velip, fostering a vibrant, localised society where these roles supported everything from daily sustenance to temple rituals and maritime trade under rulers like the Kadambas. This period, spanning from ancient Iron Age settlements around 1000 BCE through the medieval Vijayanagara and Bahmani influences up to the early 16th century, saw these professions thriving with minimal disruption from rulers, as they aligned perfectly with Goa’s coastal topography, palm groves, khazan reclamation fields, and red laterite soils, sustaining the population in a cycle of seasonal harmony and cultural continuity.

Traditional occupations fostered self-sufficiency within villages by creating a localised economy where goods and services were produced and exchanged to meet the community’s essential needs. This system relied on a division of labour and strong community ties. It was the primary means of earning, with farming serving as the vocation that offered the principal source of sustenance and revenue for most people. This guaranteed food availability and security. Secondly, these occupations created vital products – expert craftsmen manufactured items utilising expertise inherited across generations. The pots made by craftsmen were used for cooking, storing water, etc. Thirdly, it was an era of mutual dependence and community economy, with different professions relying on each other, thereby strengthening the local economic foundation. Apart from fulfilling demands, these jobs were firmly embedded in local customs and traditions, aiding in the preservation of heritage and promoting robust social frameworks. Moreover, these occupations maintained environmental harmony, utilising locally available resources to meet basic needs sustainably.

The origin

These occupations trace their origins to prehistoric and ancient times, with evidence of specialised labour emerging during the Neolithic period (around 3500 BCE) through early agrarian, fishing, and craft activities among indigenous Austric and Proto-Australoid tribes like the Kharvis and Gaudas. By the Iron Age (circa 1000–500 BCE), trade networks under empires like the Mauryas and Satavahanas formalised many of these roles, integrating them into maritime commerce (e.g., fishing, salt production, and metalworking) via ports like Gopakapattana. The Vedic varna system (1500–500 BCE), introduced via Indo-Aryan migrations around 1700–1400 BCE, further structured them into caste-based (jati) professions, with artisans and labourers often falling under Shudra or outside-varna categories. In Goa, this evolved under local Gaumkari village systems (pre-200 BCE), where communal land management supported farming, toddy tapping, and crafts tied to palm and coconut economies.

Pre-colonial rulers like the Bhojas (2nd–4th century) and Kadambas (4th–7th century) patronised these trades, emphasising agriculture, sculpture, and metallurgy. Portuguese colonisation (1510–1961) suppressed some (e.g., idol making) but preserved others through converted Catholic communities, retaining occupational endogamy.

The trend

The Portuguese invasion in 1510 signalled the beginning of decline as colonial strategies favoured export-driven cash crops and enforced land auctions, among other measures, yet numerous occupations endured – frequently modified by converted communities – offering vital roles such as baking (padeiro) and kasar/tambat within the colonial system, albeit with diminished independence and mounting economic challenges due to imported products that weakened local artisans.

Following liberation in 1961, the path altered drastically towards a downturn amid swift modernisation as Goa’s economy shifted from its agricultural base – where farming and allied occupations once supported 70–75% of the population – to mining expansions during the 1960s–70s, booming tourism beginning in the 1980s, and eventually service-sector prevalence by the 2000s, which attracted youth away from rural labour and crafts to urban employment, Gulf migration, or hospitality work. This shift led to neglected paddy fields, deserted salt pans, and a 2011 census revealing agriculture’s share in employment had diminished to 10%, with pottery and weaving falling to just 2.5%, and projections for 2025 suggesting further declines below 5% in fundamental traditional roles, attributed to real estate interests in converting non-settlement land, climate effects on coconut production, and the risky nature of occupations, like toddy tapping, which discourage younger generations.

By the 2010s, initiatives such as Pantaleao Fernandes’ 2015 publication drew attention to crafts as vanished or endangered, with artisans like mithgaudis confronting competition from industrial products and Xetkars struggling with low rice prices, cattle menace, sewage, and workforce deficits, alongside ongoing emigration patterns. Today, these occupations teeter on the brink of cultural obsolescence, with only pockets of resilience – such as ramponkars adapting to eco-tourism, or a few remaining kumbhars exhibiting their products at village fairs, or a few farmers doing rice farming/horticulture, or a few rendeiros doing the arduous task of climbing coconut trees to provide toddy to make tasty sanaas, coconut vinegar, feni, and palm jaggery. There are prompting calls for agricultural revolutions, youth incentives, and khazan restoration to blend tradition with sustainability before these irreplaceable threads of Goan identity fray beyond repair.

(The writer is a scientist and a freelancer from Taleigão)